By Federico Perelmuter

To inhabit an institution—a school, college or university, a newspaper, a foundation or NGO, a political party—one must efface individuality in favor of the traits that the institution expects from its members. Certain attributes, actions, languages, when carried out correctly, grant one access, but they must continually be upheld lest credentials be revoked, and you cast out and/or punished for transgressing. Some are aware of this fact, know that their passport will only open doors so long as they continue acceding to demands that are never transparent but always evident and clear. Women, queer people, people of color, many immigrants (some of us more aware of this fact than the rest) get the boot if they can’t demonstrate to the gatekeepers that their provenance is righteous and desirable, if the institution and its members simply tires of them. Some are not removed but trapped by their reliance on the institution’s wealth—the only thing institutions can offer—or by some hope against hope that the hellish location will change. Many aren’t aware of the conditional nature of their inclusion—ask any white man, no matter how left, who’s never left the academy if you don’t believe me and see the rancor with which they defend their place, how they see themselves as one with the institution as if their body and soul were seamlessly infused into its rhythms and demands. If you fit somewhere snugly enough, what’s to say that that place wasn’t designed just for you? They were, of course.

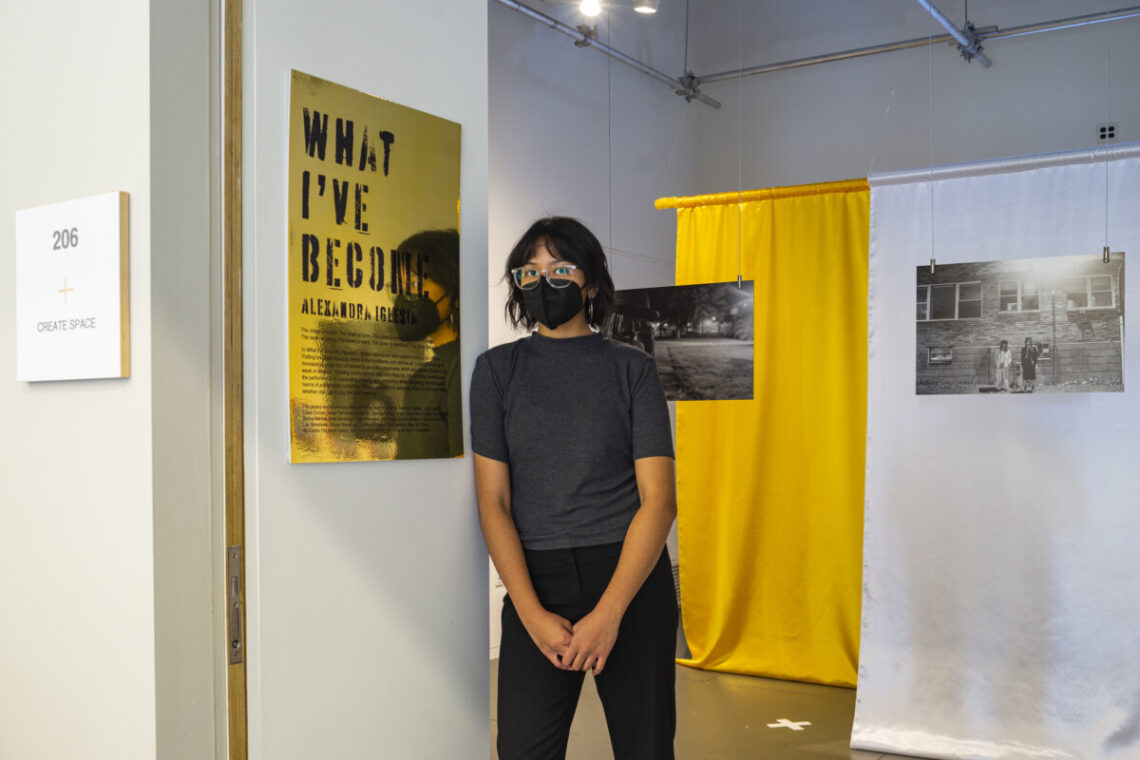

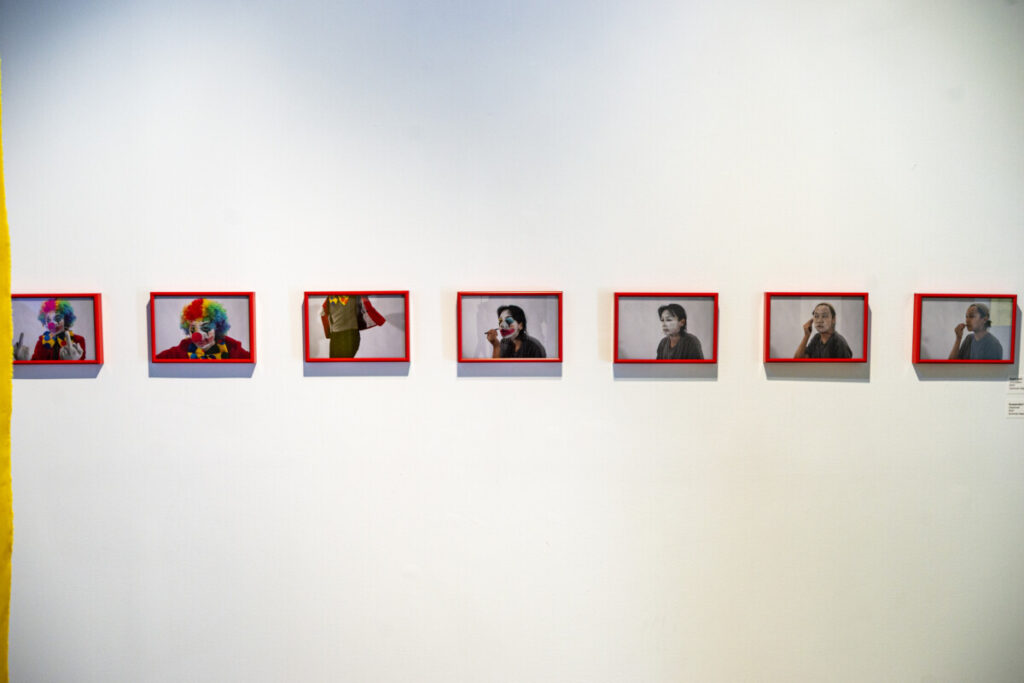

In What I’ve Become, Alexandra Iglesia reflects on the particular contortions places like Haverford College demand of students of color who hope for some participation in its resources. Through the figure of the clown—claimed most famously in the work of artists like Bruce Nauman and Cindy Sherman—Iglesia recapitulates the affective structure of ongoing interpellation and institutional extorsion, of being under the eye of an institution constantly making demands upon you, singling you out and reminding you constantly of your incapacity to fully enter and their capacity to perpetually reject you. These are the horrors of interiors, what institutions hide from their consumable visages. Through photo sequences of her and Alice Hu, a collaborator, putting on clown makeup to evoke the meme of that name, Iglesia excavates in time the alienation that they experienced as a student. Humor blends tragedy into a campy abjection evinced by the weird admixture of levity and sorrow in both performers’ faces. Depressed funhouse installation and critique of racial violence and institutional demands for the effacing of students of color, Iglesias’ expansive multimedia piece fashions a new language through which to weigh the myths and legends—lies all—through which Liberal Arts Colleges and other similarly progressive institutions built their patrimony and use to hoard and balloon it. Moten and Harney wrote in The Undercommons: “It cannot be denied that the University is not a place of Enlightenment,” and Iglesia asks who was fooled into believing otherwise—they who came here, or an institution incapable of including without traumatizing and essentializing, without violence?

What remains is a twisted sense of excess, the joyous weight on the soul of the pained. The weight of an institution or two. Below is my interview with Iglesia, early in a November night, on Zoom.

Lex: There’s something that I’ve been thinking about as an artist, about what I want to do in my work, and that is to create a line of longevity and legacy for my family and my own familial history, that doesn’t necessarily mean creating a pocket in, I don’t know, a big old history book dedicated to my family or whatever, wherever that could mean. But just like literally promoting the idea of longevity and like it’s just, this thing happening with my family right now is making me very pessimistic and making me feel really like, well, longevity is like really a hard thing to come by. Like, that is what you want.

Fede: What do you mean by longevity like this? Is it an archival impulse? Is it that you want to leave record?

Lex: Yeah, leave record. Yeah. But how could you leave record if my family’s continuing to break apart, you know?

Fede: But at the same time, isn’t the breaking up itself the record in a way? Haven’t you spent all this time thinking about those break-ups? About the brokenness of that record, because at the same time the record only existed because of that brokenness.

Lex: Yeah, yeah. There’s like resistance and sustenance in brokenness, which is an argument that I’m really for. But also, I can feel like the forces are really against me sometimes, living in a liberal empire in the “mainland,” even though, you know, empire’s pretty much everywhere, US empire. It’s so strong, it’s not even like you’re looking at an advertisement or you’re looking at social media where your interactions with the empire happened. It’s literally through interpersonal relationships and everyday conversations. And it gets hard, every time you socialize with someone. It’s just hard to advocate for brokenness in a society that really prioritizes purity.

Fede: Brokenness and purity, as opposed to wholeness. Although wholeness is implicit within purity, but purity is a kind of smoothness, right? A kind of perfection. Whereas, I don’t know, I feel like every time I hear white people like talk about how they can trace their ancestry back to, whatever, Alexander the Great. You know, it’s like cool but I can’t, you know, I know who my great grandfather was, but not even, I know his name but we don’t know anything about him.

Lex: Yeah, totally. I feel like I cite him every time I talk, but he’s just so influential. Fred Moten’s In the Break is a hard, hard text to read. And the reason why the work is so hard is because he’s creating a language that you have to learn how to read while reading it. So, it’s about really committing yourself to the struggle of doing that work.

Fede: I’m really curious about this concern you have, which we talked about elsewhere, about your own intelligibility, about what it means to have a relationship with an audience and how abstract or concrete that can be. Where is your thinking about that, maybe in relation to this archival impulse? Because an archive is only an archive insofar as it is or isn’t read, or rather exists as the potential to be read. How do you manage that tension, if you do?

Lex: This is something that I think about a lot, and I think so do a lot of artists who come from marginalized positions: balancing this tension between being “elite” and wanting to make work for an “audience” that comes from a background with less schooling or from poorer backgrounds. Right? So I think I have two answers to that question. One is that I really love the people who are part of my community; I love my family so much, even though I have a lot of beef, because for me it’s about committing to doing this complicated work. Life itself is really complicated and there’s a limited amount of mediums available to us in which to articulate how complicated. I think it’s because I have a love for where I come from. But then also it’s like really committing to–see, I would even hesitate to use the word vernacular, which is really weird to me because it’s a word that I’ve used a lot in school and whatever. But before school, I didn’t know the word vernacular itself, but I knew what a vernacular was, I knew like it was an ordinary language. And I think it’s important to engage with social media and the internet, to connect with mass culture.

Fede: But how do you enact that? There are a lot of ways, right? We’ve talked about about Legacy Russell’s work before [and her book Glitch Feminism], and one thing she does think about is the persistence of racialization online and the ways in which it manifests not only in terms of infrastructural surveillance, but also the internet as a social space or entity. How do you see that relationship, where is it? What is it like for you? Internet-speak, if you will, includes memes of which, you know, the show makes very deft use like. Are those already part of whatever you think of as your vernacular, a certain vernacular that you’re you’re working in? Or are trying to blend two previously unrelated things together and see what happens?

Lex: Would I say that I’m creating something new of it? [sighs] No, but maybe something more of a regeneration, like…can we pause that question then can we come back to it?

Fede: Yeah, yeah, we can come back to it. OK, let me move to a slightly different question then. We’ve been talking about clown theory a bunch as a joke, but then you took that seriously. Did you find something interesting in tying clown as a history and a tradition, as a vernacular and a form of popular art? Even if it is in some way a European tradition, though in a lot of ways it isn’t. How you connect the clown to a theoretical question, to the word theory itself. How do you see your work’s relationship to theory, perhaps?

Lex: I had no idea what clown theory was until like I looked it up, obviously, until we talked about it. And I guess it’s a joke that I’m taking seriously. Not really like, oh, we started off as a joke, and now I’m taking it seriously, but it’s a joke that I’m taking seriously, if that makes any sense.

Fede: I feel like taking jokes seriously is…

Lex: Kind of the whole project.

Fede: And a tradition.

Lex: Totally. Yeah. Yeah, I wanted to basically disregard a lot of Lecoq’s clown theory. He argues for creating your own unique clown face and leaning into laughing at yourself in theater. Perhaps I’m not throwing that all away, but really, I’m just trying to converse with it and create a different visual rhetoric in What I’ve Become that’s more cynical and perhaps more paradoxical. Because Lecoq’s theory is about creating your own unique clown face and exaggerating one of your own emotions. But the vernacular definition of clown and clowning is ever-changing. Think if you remember–not to cite electoral politics–but Joe Biden used the word clown multiple times in a debate against Donald Trump to describe Donald Trump and to really kick him off the stage. And that’s one contemporary definition of the clown. But there’s also this definition of clowning that I use in like social circles: “oh, we’re just clowning each other, we’re just clowning around. We’re just joking around” or someone says something funny, and you just call them a clown, but it’s not anything sinister like Biden was doing with Trump. I wanted to create a rhetoric of copying, concealing or pretending, which is something I include in the introductory panel. And that is not really doing the opposite of Lecoq’s theory but doing something else. I just wouldn’t put a unique and copying as opposites.

Fede: Why wouldn’t you put unique and copying as opposites? Can you say more?

Lex: Because a copy is in itself unique, right? A copy is unique of the first unique thing. If you think of it in that way, then they can’t be opposites.

Fede: Right. Because there is one tradition of the clown as the return of the repressed, like in King Lear, the Fool. Both in your show and in Lecoq’s theory the clown is this, in some sense, ultimate assertion of the performance of individuality. But in another way, in that exaggeration there’s a critique of an emotional experience that is constructed and naturalized. I’m curious whether that aspect of the clown was on your mind and how you tied it to institutions. Because they are often framed as microcosms, you know, little isolated worlds. Obviously, that’s not really true but I’m curious about how clown was useful for you to think about institutions?

Lex: Yeah, I think this is a great time to really make a distinction between the performativity and performance. Temporality is a key part of thinking about this difference between performativity and performance in that performativity is really like a way of being, a way you’re socially constructed to be. And then a performance, you put a performance on in a limited time and space. I wanted to blur the lines with this project, and felt like the clown as an affective structure, as an allegory of institutions or of the way that I’m gendered and racialized in institutionalized spaces was just a more fun and weird caricature. For some reason, I’m really drawn to creating caricatures, and I think that’s just because I try to find ways to visualize or realize things that tend to elude representation, which are typically like forgotten about or overlooked. I try to do that in a more character…I really don’t know another word for character, but just a more vibrant way. So that’s probably why I picked the clown.

Fede: What do you mean by vibrant?

Lex: Something that I think about a lot in my work, and just like as a person is like invisibility, visibility, and hyper-visibility. Not really thinking of those three things on a spectrum, but just thinking of those things as this braid where I have to jump between the strands. Something vibrant can be all three of one, if you really think about it like that, it can really stand out like a highlighter, so hyper-visible. [Pauses] Sorry, I’m really tired…Or it could just be seen as a vibrant color amidst other colors, or you can turn away, and thus it will be invisible because it is too vibrant. I guess that’s what I mean when I say that I chose the clown as a vibrant visual figure.

Fede: Which is interesting because that resonates with Moten as well, right? The idea of the blur.

Lex: Mm hmm.

Fede: Perhaps relatedly, I feel like in a lot of ways the show is deeply funny and deeply sad at the same time? Like the first time I saw “Recruitment,” when the character you play, the clown, the already recruited, already performing clown, if you will, gives the other character [played by Alice Hu] the box. You have a facial expression that is hard to distinguish, but it looks like a laugh. And perhaps it is, and perhaps it isn’t, and the uncertainty there is a very interesting part of it for me. Where do you locate humor in the show? And perhaps that’s two sided because, on the one hand, it’s laughter, but on the other hand, it’s levity, right? And non-seriousness or an approach to a certain kind of brokenness, to go back to the very beginning.

Lex: When you first sent me this question that you just ask, you actually used this phrase: “I saw recruitment and I couldn’t stop myself from laughing out loud because of the absurdity and the strange cheeriness of your clown makeup.” And I was thinking about a strange cheeriness or just cheeriness and it’s really fascinating to me that you can’t get cheeriness without eeriness. That really [laughs]…not to play on words like that, but I think that really describes—oof, hard word—aesthetically what the facial expression is. It’s like, what is this cheeriness that is forever haunted by an eeriness. That’s what I’ve been thinking about in my work in general and I’m constantly negotiating between humor and like deep sadness. A genre that I’m really drawn to is horror comedy, and I think it’s because it’s contradictory in nature. In my work, I’m trying to encapsulate the complexities and the ambivalence of my life as a subject an empire. You use humor to resist that deep sadness, but you can’t just ignore that sadness because that’s always going to be there.

Fede: Yeah. Yeah, and the other side of that is precarity, right? I think sadness is not a precarious emotion, it’s not one that I really have to take care of, it really does just kind of happen. But happiness is so ephemeral. Another thing that your show captured is that sense of emotional comfort or rest. Because that seems to always be kind of just out of grasp, just out of reach?

Lex: What’s also precarious in the film and in the work is the makeup itself. Like the makeup we see is a rushed effort, and it’s extremely uneven and it was actually really difficult to get that white makeup onto my face, like the photographs and the film don’t really capture the amount of time it took to put that white shit on my face. But there’s a precarity in the joy of pretending. And I think that’s really fascinating to think about, how it shows up in the work and how people read the work.

Fede: What do you mean?

Lex: I think make-up obscures my facial features and my skin, but only for a short amount of time. I was filming and making the photographs in front of lights, and I was biking around a bunch of times and it was in the summer and it was hot and humid, so I was sweaty and the makeup was literally coming off my face while doing this weird thing of also obscuring it at the same time. And just knowing that my face is how it permanently is, I can’t really *change* change it unless I do plastic surgery or permanent skin whitening. Well, again, makeup doesn’t have a permanence like your facial features and your skin do. It’s an easy thing to think about, but also it’s an overlooked thing to think about.

Fede: That ties to a key facet of the show or rather the context. Clowns in the past 10 years have had an outsized importance in film, especially. You know, Joker, but there’s also It, The Dark Knight, whatever, you know, all of these versions of the clown where they seem to be narrating this vaudeville-adjacent play on racialization. Where it goes, “Oh, white men…We’re so oppressed” and they attempt to materialize a certain kind of oppression, but then restrict it. So that it’s not really a critique of the kind of structures that produce the misery that is being depicted, but rather reoriented towards the white male subjects that feel themselves to be endangered. Was that on your mind? We’ve talked about Joker being pleasurable for you in some way, which it definitely wasn’t for me, and I’m curious about where pleasure lies in that performance for you?

Lex: I suppose with Joker, I found a lot of pleasure in the fictitious nature of it, a story that is ahistorical and also completely disregards the structure of racial capitalism. I get the pleasure of critiquing that with you and then thinking throughout the movie. And then I also find pleasure in forgetting about the horrors of being a subject of racial capitalism in this Hollywood film, like I feel a lot of people do. I don’t really have anything too smart to say about that. My thinking about Joker in particular, in regard to What I’ve Become, came much later than when I was thinking about Stephen King’s It, which is really fascinating to me. But I think it’s just because of the way timelines lined up. When I was in high school, there were these people who dressed up as clowns and scared people across the suburbs of New Jersey and Pennsylvania… It was really absurd. There was this intense fear of the lonesome clown figure. That fear stems from racializing an outsider, the one who is different. I myself was scared; I have to admit that I was literally scared of being pulled into a sewer. But I think now developing this understanding or unlearning that fear and obtaining the language to name where it came from made me lean into it and become a rebel in a sense, lean into the person that white people are scared of. I mean, I was also thinking about Cindy Sherman’s clowns. And her work in general relates back to the dark history of minstrelsy and blackface and brownface, because she actually did those, but obviously it’s different for a white woman to do that than for a brown-skinned Asian person to dress up as a white-faced clown. I was thinking a lot about the comedy from 2004, White Chicks, and how there’s been a conservative, fascist rhetoric of reverse racism with that film. I wanted to invite the people who are looking at the work to think historically when it comes to race. And really taking on the work to think with more nuances than see-sawing back and forth on a racial binary of black and white. I was also thinking about Bruce Nauman’s “Clown Torture” and Paul McCarthy’s “Painter” as performances in predominantly white spaces like the art world. They have ways of creating a disturbing hilarity in their work. I was deeply inspired by that, and I was wondering what that would look like for someone like me and someone like Alice [Hu, the other performer featured in the show] because we’ve talked about their work together. There are a lot of different reclamations of the clown figure, like clowncore, this whole internet community that really advocates for dressing up like a clown every day, which is super cool. But the reason why I tried really hard not to use the word clown in my introductory panel, besides citing the “Putting on Clown Makeup” meme is because I wanted to think with the affective structure of the clown and make my own definition of it based on my experiences at Haverford.

Fede: What do you mean by the affective structure of the clown?

Lex: So, OK, let’s go back to what I mentioned before with the clowns all over New Jersey and PA, who were just were standing by themselves and scaring people. Yes, there’s an inherent fear and othering in looking at that clown. But also, I was thinking about why those people were doing that in the first place. I was thinking about loneliness (hopefully not in angsty teen way, which is something that I tend to do), but thinking about loneliness in literally growing up in the United States of America, and this profound avocation to and dedication to individualization that American institutions really put you through and the intense loneliness that you feel through that. I was thinking of that as part of the affective structure of the clown, but also the joyfulness of dressing up as a clown. And then when clowns are together, when clowns like hop out of a clown car, there’s this collectivity and recognition of individualization. There are separate parts to the clown car, or not separate, but really different parts that were together separately in this weird tension of separability in a circus.

Fede: I do want to ask you think back on that question we put on a pin about the relationship between vernacular and the Internet. Perhaps one way to approach it, at least partly, is through institutionality. What do you think the relationship between institutions like Haverford or art museums or academia in general or whatever other institution and the Internet is?

Lex: I think something that all these different spaces…I’m using space to describe the space of the Internet, bceause I haven’t come up with another word for describing it as a social space. Institutions and the art world and the vernacular all have something in common in that they all have inside jokes, which is really a funny way of thinking about interiority and exteriority. Within those spaces, you have a way of speaking to the other people in those spaces. Thinking across them would mean taking on the work of code-switching. What code-switching is and language learning in general, what sorts of language do I have to learn when I shift from the vernacular into an institution or art museum into Instagram? Those are just different ways of inhabiting a performance. In your question of how to connect institutions like Haverford College and the Internet, I’ve been thinking about what does justice *look* like versus what is justice? That also plays into the performativity aspect of it all, if you’re performing justice or you’re actually acting it. Yeah, that’s just the question, I don’t really have an answer for that.

Fede: Those same tensions of visibility and hyper visibility we were discussing, perhaps another word is display? I feel like it’s so intensely at work. In museums, but also at institutions and especially online, when you go on their web page and you see the classic pictures of one student of color and three white students and they’re all kind of laughing and all that, it’s this work of display. Which is interesting because it ties back to something that Internet discourse can offer or obfuscate for thinking about these institutions. So much of it is about how to render oneself visible or understood or about constructing a persona. I’ve asked you why you’re not on Twitter anymore, we’ve discussed the exhaustion of having to produce yourself over and over in some recognizable way.

Lex: There’s this idea of rest in being invisible. The connection between being on Twitter and being at Haverford is finding ways to be visible in on a platform. It is exhausting in a way, but I want to refuse the idea that there’s rest in invisibility. When you think of rest, you think of sleeping, but what if you can’t rest because you have nightmares, and that usually happens in spaces that aren’t really seen. The way to work through those nightmares has to be committing yourself to wanting to be visible. It’s kind of what I’m doing in the project, and thinking about the past tense of the title, What I’ve Become…I want to invite people to do the work to think of it historically, which is exhausting in a way. To really think about a violent or Orientalist past for this one person or two people, and therefore a fuck-ton of people who have tried to work their way into American history. Yeah, I guess that’s all I have to say about that. I mean, what is this idea of rest? Like what are different ways we can think about rest that aren’t just constantly trying to render yourself visible to then be exploited, but rather visible to hold a presence in a space. That just goes back to the first thing that I said to you tonight, of trying to sustain legacy and do the longevity thing for my family. I think I just talked, and it was one big circle.

Fede: This is a nice place to end, I like ending where we began. And I feel like there’s something to the show that is that, right? That past tense, that becoming that we’re watching in the film and in the pictures, at the same time the show itself is already telling you yeah, this happened already.

Lex: Yeah, I want to really specify the tense that I used and make a difference between becoming as implying something in the future, that something’s going to happen in the future, versus have become which is present perfect tense. And yes, that shapes that something has already happened and continues to happen to this present moment. And I really want to advocate that our subjectivities have been really shaped and are residual of this wartime, Orientalist past.